Erecting and managing mobility data platforms involve design choices. Designers are no neutral actors, but operate within a hierarchy, a market, a network or a mix. In other words, designers operate within a context wherein both technology and social interaction play an important role. They design rules that guide behaviour (institutions). Their own behaviour – i.e. their design choices – are also subject to institutions.

Keywords: design, socio-technical systems, institutions, embeddedness, arrangements

Getting to smarter mobility involves a creative process wherein designers play a prominent role. Designers obviously create technical elements, such as algorithms, user interfaces and hardware. Design also involves social elements, such as data delivery contracts, agreements about privacy, and platform management. These technical and social elements for design may interact, for instance when algorithms are designed to respect privacy.

In other words: smart mobility involves designing socio-technical systems. Designing a socio-technical system includes designing technical artefacts and social rules that guide behaviour. These social rules are often called ‘institutions’. To be precise: institutions are rules that guide behaviour. However, not every rule is an institution. They have to be accepted by both developers and subjects to rules, they must be used in practice and they must endure for some time (Goodin, 1996; Koppenjan and Groenewegen, 2005). For further discussion on the precise definition of institutions, we refer to Menard (1995).

Is it up to the designers to make institutions? In fact: partly. Institutions are also a context for designers. They for instance just do not have the position to design laws and regulations. As such, these laws and regulations form conditions for the design, either the ‘design space’.

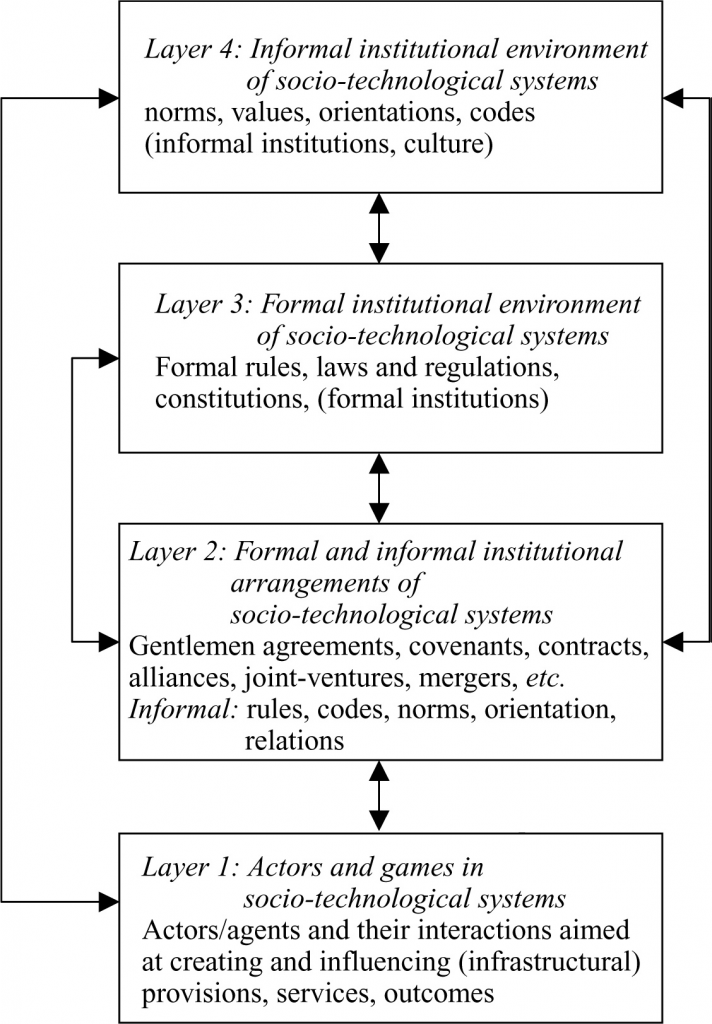

This dynamic is addressed neatly by institutional economists. They have made typologies of institutions that are useful for understanding design of and in sociotechnical systems. We mainly refer to the typology of Williamson (1998), reworked by Koppenjan and Groenewegen (2005) with a focus on complex technological systems. It sketches four layers of institutions, each representing different types of institutions, and different positions of designers.

A first layer involves actors and games in socio-technical systems. This layer represents everyday transactions within the context of a market (f.i. trading), a hierarchy (f.i. obedience), or a network (f.i. tit for tat actions). Rules to be considered here are visible as practices, as volatile as they are.

A second layer represents formal and informal institutional arrangements of socio-technical systems. Formal arrangements are visible on paper, for instance in covenants, contracts, agreements, etc. Informal arrangements are less visible, but may structure behaviour as well. They are norms, routines and codes that emerge in relations between actors.

The third layer forms the formal institutional environment of socio-technical systems. These institutions are visible in laws, regulations, and constitutions. They usually cover more actors than second layer institutions and they are more durable, if it wasn’t just for the simple reason that they require more effort to change them. For instance, changing laws take lots of political and bureaucratic effort and is – as a result – time consuming.

Finally, a fourth layer involves the informal institutional environment of socio-technical systems. These are again not that visible as formal institutions. They are rules of culture, of societal values. They surely guide behaviour, however it is hard to pinpoint where and how. Changing these institutions is a barely purposeful, collective effort that takes many years.

Figure 1 visualizes this typology. It also suggests that the different categories of institutions influence are not isolated rules. They rather influence each other over time.

Figure 1: Four levels of institutions (source: Koppenjan and Groenewegen, 2005)

What does this mean for designers? The main dimension behind this typology of institutions is their level of embeddedness, and as a consequence the time and effort it takes to change them. This means that some institutions are more fixed than others. Some rules are a given for designers, effectively serving as prerequisites for their design. Others are subject to their design.

In other words, the designer’s job is twofold: designing of socio-technical systems and designing in socio-technical systems. This duality has several very practical consequences that is worth a reflection.

First, there is no one size fits all smart mobility solution. Each city or region may have its own institutions that designer should accept as a given.

Second, there is no such thing as designing in isolation. One has to know the institutional environment wherein a design has to fit.

Third, and related, this story about institutions suggests that designers have a moving target. Institutions may be volatile, so design may create new institutions and change existing institutions, even unintended. New relations are created and new norms and behaviour emerge.

Mobility data platforms are designed in an institutional context, with a large part of that context unavailable for change to the designers of the platform. This means the governance of the platform has to be designed within this context and has to align with it. As these contexts are widely divers, from data protection to mobility policies, a single answer is largely unavailable, but a better understanding of the dependencies between mobility data solutions and the institutional context and governance options is key.