Our cases indicate that cities with a transport authority are generally more ambitious as well as more successful in smart mobility projects. This can be explained by their functional dedication to smart mobility as well as their hierarchical position to request data.

Keywords: transport authority, integration, hierarchy, reciprocity, data requests

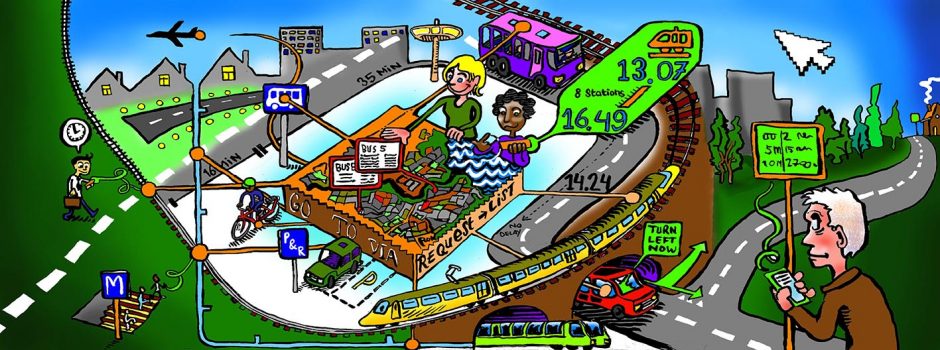

Anything you give attention to, grows. Flowers, food, human performance, but smart mobility? Who has the perseverance to spend huge amounts of time and attention to a thing as smart mobility? Who is so dedicated to transport, ICT and public space at the same time? Our studied cases clearly suggest that integral transport authorities are the most obvious, and perhaps the only, candidate. In many cities an integral transport authority is in place. Our cases indicate that cities with a transport authority are generally more ambitious as well as more successful in smart mobility projects. London, Melbourne, and Helsinki are the main cases where the transport authority has the journey planning platform. In the Netherlands and Stuttgart the platforms belongs to a consortium between authorities and operators.

The reasons for this may seem obvious. These are functional authorities, tailored to improve just transport and mobility issues. This means that they have to make little tradeoffs to other issues than mobility. They seem to be natural actors to request data and process them. They have the knowledge needed to do so. This knowledge includes both technical and institutional knowledge. They organize the transport markets and lay down the incentives to provide data and improve mobility. This is, of course, as far as their competences go. Some transport authorities are specialized in public transport – such as in Rome – others cover also private modalities – such as in the Vienna Region.

There is also a geographical aspect to it. Some authorities cover a city, others a metropolitan area, others a wider region. Transport authorities are dedicated to improving mobility. This makes them a considerable integrative force. If an urban area lacks such a transport authority – such as Venice – integration of modalities and data gathering from several parties can be much harder.

Is it as simple as that? Is the success of smart mobility determined by this fact of having a transport authority with competences that fit the ambitions of the project? It helps, of course. But no, our cases show that even an eventual match between project and authority at the start may not endure. In Vienna the smart mobility initiative eventually extended the competences of the transport authority that stood at the cradle. In this case, the transport authority shows a willingness to cross the functional and geographical line of their competences. This is a big step for them. Crossing such a line comes at considerable transaction costs, including coordination efforts with other authorities in which they become a requesting party.

In sum, we should distinguish two forms of dedication. Transport authorities dedicate their time and attention along with their formal mandate, as defined by the functional and geographical competences and jurisdictions. There is also a behavioural dedication, based on the willingness to look beyond these competences and jurisdictions. A remaining key question is: If transport authorities are eager to support smart mobility projects even beyond their formal mandate, what is driving them?

The most notorious advantage for a transport authority to engage in smart mobility is not to improve transport, but to improve authority. What’s in a name. A transport authority needs to be in power, like smart mobility platforms have a continuous thirst for data, i.e. from mobility providers, from telecom operators, from event organizers, from the police, etcetera. On whose behalf are these data requested? The answers to this simple question may differ per city. In Rome the transport authority RSM is able to back their request with formal authority. Venice lacks such a transport authority. The smart mobility initiative is a responsibility of AVM, a holding company for all municipal transport providers. They lack this authority and will have to explain twice why they request data and what they will do with them. In other words, they have to request data in a networked context where authority is not a given but a continuous, multifaceted game of give and take. In such a context, transactions are based on reciprocity: you do something for me, I’ll do something for you. However, what can AVM do to for instance for the police as compensation for receiving the data? This illustrates again the practicality of a transport authority. It seems some amount of hierarchy is important here.

We started off with love, but we seem to end unromantically. Yes, smart mobility grows with love and dedication. However, love and dedication sometimes is a given. And worse, it is not enough, also authority is vital. Unromantic, but real.