The operationalization of public values for large-scale innovation processes is an intricate process with iterations and changes to be expected. In practice, the operationalization of public values appears quite a bureaucratic or technocratic endeavour without much public debate or political involvement. This is not necessarily wrong, but it brings governance risks.

Key words: public values, trade-offs, user involvement, policy process, evaluation

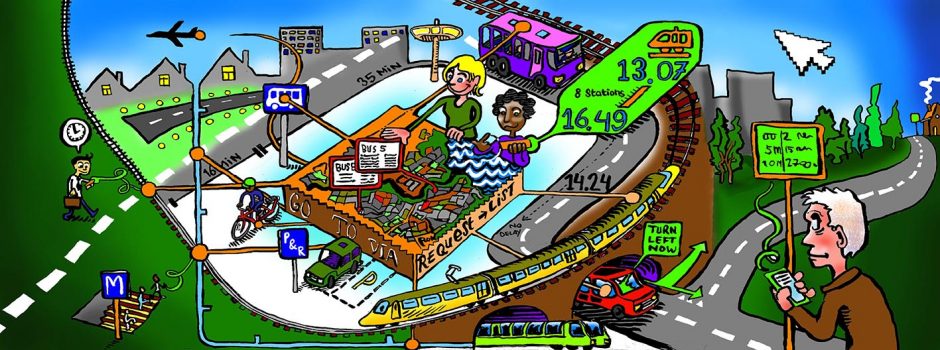

Public values are important drivers of the innovation in intelligent mobility. A public value, to put it simply, is ‘what we want’. But what do we really want? Think of an old fashioned public value like a city’s accessibility or public efficiency, or a more recent one like sustainability. It often is a mix of public values that drives major innovations. An interesting aspect of innovation is the uncertainty. Although we seem to want it, we don’t yet know what we will get. Hence, in the meanwhile, until we ultimately achieve something new, we can’t yet tell if that is what we really want. We could call it the Frankenstein-trap. Hence, innovations require constant or at least repetitive reflection. Is this what we really want? Public values require gradual operationalization and even radical reconsiderations should be thinkable. How does this process work and how is it facilitated? Governance is key to this.

In general, the operationalization of public values can be understood to co-exist in four interacting stages: advocacy, politics, bureaucracy and provision.[1] People advocate for certain public values. Politicians acknowledge and negotiate certain values. Bureaucracy further specifies certain values. Finally, companies may provide services that meet certain public values.

In the studied cases, we do not see a very rich process of operationalizing public values in this respect. There is often little politics, little advocacy and little provision. In the London case Plan a Journey, for example, like many other developments within transport authorities, the operationalization of public values seems mainly geared to the ‘bureaucratic stage’. A probably related observation is that the public values driving these developments more often than not come without a clear target to actually provide services.

In the EU-funded projects, public values seem omnipresent, but their operationalization often remains neglected or hidden. The main project objectives, for example, are typically neither oriented towards nor responsive to a broad, reflective and interactive process of operationalizing public values.

The experience at Mobidot – a smart mobility software provider in the Netherlands – is that municipalities are generally reluctant to specify public values. What is the desired mobility behaviour to stimulate? What should be considered green? At the political level, the risk of reputation damage is mentioned as a main obstacle. Many specifications have a downside or a trade-off. At the bureaucratic level, the ingrained key performance indicators are mentioned as forces that keep municipalities from specifying new public values. Compartmentalization is also mentioned as a factor. It means that fractions within municipalities are used to and prefer to do their task as independent as possible, department by department. Innovations in intelligent mobility, however, typically bring together municipal departments and force them to cooperate. This often triggers explorative cooperation processes between departments that remain slow, noncommittal and nonspecific. Hence, public values often remain underspecified at the level of municipalities. Therefore, for the time being, provisional specifications are often made in a technocratic context by experts outside government. Possibly, these specifications appear controversial in five years or so, but for now few questions are asked.

To conclude, the operationalization of public values driving the innovation of intelligent mobility appears quite a bureaucratic or technocratic endeavour without much public debate. This is not necessarily wrong, but it has clear risks. How do we know if this is what we want? To answer this question, public values need to be contested. Little questions are asked about who ‘we’ should be. ‘What we want’ is suspiciously uncontested throughout most innovative projects studied here. This might imply two things. First, if public values are not contested, they are probably not public values. In this case it would be questionable if governments should be initiators of these platforms. A second implication could be that ‘we’ are still asleep, until incidents happen wherein public values – such as sustainability, privacy, and public efficiency – appear to be harmed. In such a case, public values will be topic of a – generally politicized – evaluation study, where the platforms will be under public scrutiny. But in such a politicized situation it is commonly questioned if we really will learn ‘what we want’.

[1] Bachrach, Peter, and Morton S. Baratz. 1970. Power and Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press