There is no such a thing as ‘one government’. A further look into government reveals multiple layers, from local towards supranational public entities, wherein authorities are distributed. At all levels problems and solutions are framed differently and collective action might get complicated. At the same time, this complexity can be a source of solutions for smart mobility platforms.

Key words: multi-level governance, layers, jurisdictions, agency, complexity

When metropolitan authorities see value in a data platform for mobility, implementing it is a sustainable way can be a challenge, because they are not the only authority in the game. Hooghe and Marks (2001) illustrate well how governmental systems have a distinctive layered characteristic, from Europe as a supra national layer through countries, regions and municipalities, and possible other jurisdictional layers. Two distinct public qualities – the agency (power to act) and the fiscalism (power to levy tax) – are distributed amongst those layers. Furthermore, this distribution drives for a large part the way in which problems are framed and consequently which public values and instruments are prioritized into policies. For example, where a municipality is confronted with the problem of unsafety for pedestrians or limited parking at the city center, a supranational government might have a different perspective focusing on CO2 emissions and market functioning. In addition, the municipality can start redeveloping the city’s crosswalks or build a car park, the supra national government would focus on emission standards and regulatory conditions.

In such a context, the way a problem reveals itself is different from different governmental levels, and this consequently will be triggering different answers. This obviously is also true for data platforms for mobility. They might align with national policies for more governmental transparency and open data. They might align with a municipal need to improve circulation of cars.

As this layered structure of government matters, a number of concepts from the literature are key. As mentioned before, ‘agency’ represents the authority a governmental body has on a certain topic. ‘Jurisdiction’ is the geographical area in which a governmental body has agency. ‘Fiscalism’ points at the way that tax revenue flows into government and is distributed over governmental layers. Unitary points at the hierarchical relations that might exist between layers, with lower levels of government expected to follow the unitary state in policy.

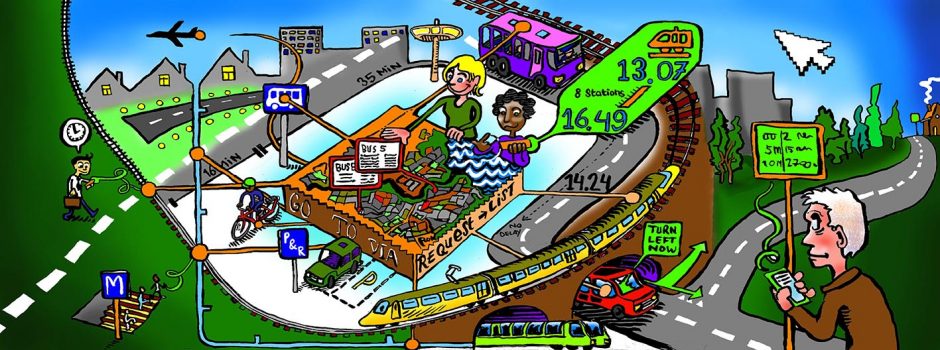

For the metropolitan areas we are dealing with a number of issues. Some mobility-related issues and solutions have clear spill-overs, scales and dependencies. A municipality hindering through-traffic is shifting the burden on surrounding municipalities, which is a negative spill-over. A metro system does only create value on the scale of the entire metropolitan area. That metro system will be dependent for full functioning on local public transport solutions: park-and-ride, bike or bus facilities, feeding travellers to the metro.

Consequently, the way that congestion is seen as problematic is different on different scales. On metropolitan level, the effect on economic development might be the first public value that is seen as under threat. On a municipal level, the high levels of NOx from stop and go traffic in a particular area might be seen as the public value under threat. On a local street, the long queues at traffic light, limiting local traffic could be seen as the public values under threat. Economic development, health and accessibility could all be aspects that could be driving the implementation, however, all in slightly different direction.

So, problems and solutions operate on different levels. At the same time, governmental layers may have different instruments that could help drive the solution. Traffic control and the related sensors could be under the control of local authorities, the contract with bus operators at a metropolitan level and the railways on a national level.

Also, authority operates in different ways. They are more fragmented or more concentrated, have a more general purpose or a more specialized purpose, are stable or fluctuating, authorize overlapping or mutually excluding territories, etcetera (Hooghe and Marks 2001).

The way in which the governance of a data platform will have to be developed is heavily dependent on these factors, and on where the platform lands. If the goals are expected to be on a metropolitan level and no organizational entity exists on that level, a principal has to be set up on a metropolitan level, for example by cooperating municipalities. And someone will have to develop and maintain the platform, for example the ICT department of one of the municipalities. If a metropolitan authority with focus on mobility exists, this entity can take up either or both of these roles. So, there is a relation between the goals of the data platform and the governance and institutions in the region. They both have scales that may align or not. This alignment in turn triggers the potential and need for a change of governance.

Finally, multi-level governance is a dynamic feature. Especially ‘agency’ and ‘fiscalism’ are shifting in the course of time. This can be illustrated for smart mobility as well. Not just the governmental problem owners of a metropolitan data platform for mobility operate on various levels. One could argue that companies like Google and MAAS are building an international data platform, also in the field of mobility with very little intervention from governments. Consequently, the potential to secure public values (like privacy) related to specific jurisdictions into those solutions can be only realized through regulation, generally realized on a national or supra national level. The more globally operating companies matter, the more a need will be felt to shift authorities towards these more centralized levels.

So far we framed multi-level governance as a source of complexities. Complexities are often seen as problems. However, the variety of layers can also be a source for smart mobility solutions. When looking at the broader picture, multi-level governance issues can drive the potential of a data platform on a metropolitan level. The to go option seems to be having a metropolitan entity, cooperative or unitary, that can drive the goals and implementation of the data platform. Four options occur when no suitable governance exists on a metropolitan level. First, the implementation can be aimed at limited goals. For example, one municipality could just start gathering the data of the various municipalities in the area have available and make in usable and useful for others. Second, a special purpose entity could be set up that sets the goals for the platform and drives it development both financially and content wise. One could think about a new cooperative body between local municipality and potentially the national or regional government. Third, a more generic integration of mobility policy could be developed, with the platform being only one of its potential instruments. Mobility policy that encapsulates the daily urban system of the inhabitants of a metropolitan areas makes sense. Obviously, the platform plays only a minor part here. Finally, data platforms on mobility are also developed by the market parties. They have an advantage as they can develop the technologies and can easily scale and adjust to various authorities. These private platform solutions could be valuable to fragmented metropolitan authorities that are lacking the governance on a metropolitan level.