Innovations like infomobility platforms hold promises. A local platform has to deal with vested institutions. Vested institutions may delay innovations. The institutional void may be filled by a global player not interested in local institutions. If a local stakeholder group doesn’t want this global player to set the standard, they must be able to look beyond their interests.

Key words: institutional void, digital platforms, innovation, vested institutions

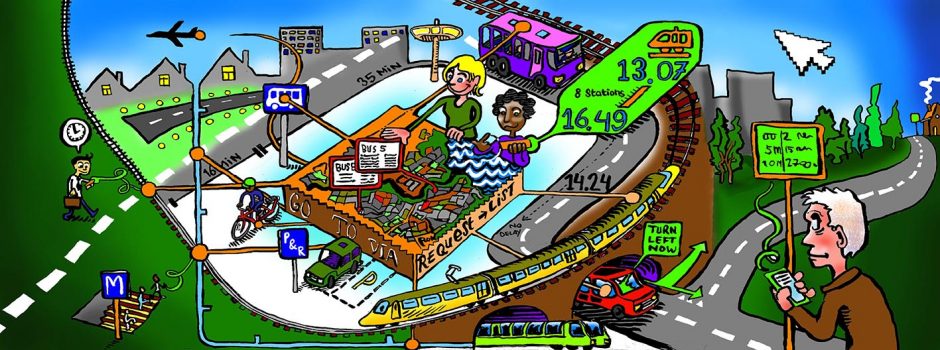

Platforms seem to be the ultimate manifestation of the network society; by connecting various groups of actors and their products, needs, data, etc. to each other, everyone seems to potentially be better of. The distributed nature of the entire ecosystem, with various parties owning the physical and digital infrastructures involved, crossing boundaries between organizations and sectors, seems to ask for parties to collaborate on the platform in order to make it work.

Governments and other actors such as NGO’s and trade organizations look at forms of (network) governance to make a difference in this networked world of platforms. However, digital innovations may impact social structures and practices faster than institutions and processes can keep up with. They might be disruptive as well. For example, the engines of the shared economy are global platforms facilitating local sharing of services. Mechanisms – let alone laws and regulations – that address ‘sharing’ for, for instance, safety and health issues are just hardly there yet. And how do local authorities get the data they need to enforce their regulation if the data are owned by global platforms? This example shows that digital innovations may question the ability, legitimacy and effectiveness of rules and institutions. In other words: digital innovations lead to an institutional void, in which governments and other actors that used to be involved in governance have limited capacity.

Institutional voids can also be witnessed in the case of infomobility platforms. ICT’s enable us to develop tools that optimize both the individual journey of a traveller as well as the collective interests and the system as a whole. However, as our cases show, the many stakeholders involved are often hard pressed to find common ground in which a infomobility platform is to be founded. Ministries, local governments, transport authorities, a host of transport providers, interest organizations, and many others, all have their own stakes, some of which are bound to be threatened by a new platform, at least to some extend.

But while groups of stakeholders take their time debating the design of the platforms and the rules of operating it, digital innovators are finding it far less difficult to move in this domain. Take Google for example, based on their extensive information position (e.g. maps, traffic information), they’ve moved into the domain of infomobility with relative ease, making use of the lack of rules and standards to set their own. Where cities and metropolitan areas are each organizing their own process and design of their platforms, Google Transit’s data standard is by now common, not just for Google, but also to exchange data between transport operators and governments, as some of our cases show. Consequently, increasingly Google becomes a provider of a global infomobility platform, which due to its wide coverage has become the de facto solution for many travellers. Obviously it neither takes into account local value diversity nor specific wishes and demands from (local) authorities. It also does not optimize anything except for the individual traveller.

As long as local stakeholders each try to develop a platform that is fully in line with their current interests, momentum is lost to the likes of Google. This does not necessarily have to be the case. 9292OV shows that when a stakeholder group is able to look beyond their interests, both petty and vested, and collectively coordinate their efforts towards a platform, it is not only possible to come up with a successful platform, but also to have Google meet them at their terms. The 9292OV platform serves to exchange and open information on Dutch public transport and as such is the key data source not only for the parties involved, but also for Google. In other words: an individual traveller may choose to use Google, but in effect uses the coordinated information of 9292OV in the background.