Addressing travellers’ needs is necessary for mobility data platforms to be effective tools for implementation of public goals. These needs of these specific users may vary between the different journey stages. Clarifying the information needs of users at these journey stages helps to better tailor platforms.

key words: journey stages, users’ needs, implementation of public goals

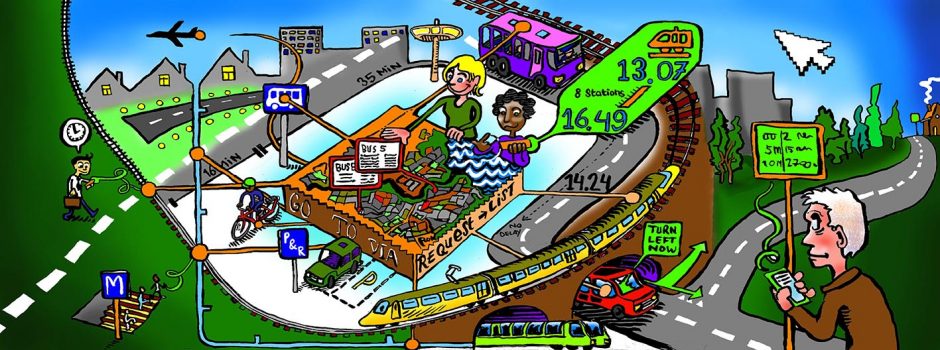

A platform for intelligent mobility should be more than just a journey planning tool. Travel information is not only relevant preceding a trip, but also during the trip at several stages, and perhaps even after the trip as well. Distinguishing the different stages of a journey and respective information needs can help identify users’ expectations.

In literature, a journey is commonly divided in four stages: (i) planning stage (before the trip begins); (ii) at stop/station stage (transference points during the trip); (iii) on-board stage (also during the trip, inside a vehicle); and (iv) return trip planning stage (Grotenhuis et al. 2007; Zografos et al. 2010). We add a fifth one: after the trip. At each stage, we can identify and distinguish different types of information needs for different types of users.

- The planning stage is typically takes place at home, a hotel or work location. Users generally value the convenience of understanding all steps required to perform the desired journey. This requires a range of information regarding the entire trip in advance: routes and modes available, need for transference between modes, duration of the trip, costs etc. Therefore both static information (timetables for instance) and dynamic information (delays, disruptions) are relevant. PTV, for instance, describes the trip step by step and also provides a graphic overview of the entire journey with a map. Many platforms also add the possibility for users to purchase tickets online in advance (Qixxit or VSS, for instance). Some users may be interested in knowing in advance the trip alternative that emits less pollutants or that brings more health benefits (CarFreeAtoZ offers this information). Two important aspects that are missing in the platforms described in this Handbook: first, if the platform includes car trips as alternatives for travellers, parking information should also be provided. Second, information regarding accessibility for people with special mobility needs – these users require details on ways to access stations and terminals as well as their surroundings.

- The stop/station stage are wayside locations comprised in the trip like bus stops, stations, park and rides, etc. The type of information required in this stage is mainly used for travel support rather than for preparation of the trip. Points of transference are of special importance as they have increased likelihood of posing challenges to travellers, both regular city commuters or tourists. Many times the need to make transferences during the trip hinders the choice of public transport modes for instance (with Plan a Journey, for instance, users can opt for planning trips defining the least number of transferences as the main selection criterion). The last travel stop can also be regarded as a wayside location and users may require advice on how to move from there to their final destination (like a map for walking as offered in 9292OV). In this stage it is relevant for users to know the time available to effectuate a transference between modes, changes in departure/arrival platform, accidents etc. Dedicated information for people with special mobility needs is also valuable in this journey stage.

- On-board information also aims at travel support rather than planning. It is the information provided during the trip and when the user is inside a vehicle. In this case information can be tailored depending on the moment in the trip: during initial or intermediary journey legs those users unfamiliar with the route may require travel alerts to indicate that it is time to get off the bus and switch to a different mode for instance. Qixxit offers dynamic information with alerts as the trip progresses. 9292OV provides static information – it lists all stops a mode makes during the planned trip (including intermediate stops) so to ensure the risk of missing the correct stop will be reduced. Stations with a connection to other modes of transportation are also points that can be informed. Tourists may also want to be informed that they are passing by a certain attraction or that a particular stop is the closest to it. Finally, availability of parking spots (either static or dynamic information) is useful during this stage.

- Return trip planning may or may not take place in all trips. Needs are similar to the initial stage and the return planning may even happen at the beginning of the trip as well. 9292OV and PTV, for example, allow users to plan the return journey by pressing a single bottom that switches starting point and end point of the trip to be planned.

- Travel information needs after the trip may seem redundant, but they can also be relevant. The platforms we studied did not focus on this stage. How far and how long did I travel? What did it cost me? How much did I pollute? How does my performance relate to the other options I had? Did the planning correspond with the journey?

Looking at the different journey stages may support authorities when designing a platform by helping them in the identification of the features needed to respond to users’ interests at each stage. These interests may be multiple: they can be individual – time saving, cost saving, effort saving (all of them during the search process and also for the trip itself) – but also collective – reduced overall pollutant emissions, reduced overall traffic congestion etc. In any case, clarity on these expected benefits is needed so the platform can be designed and tailored accordingly. Attracting users is a necessary condition for authorities wishing to use their digital platforms as an effective policy tool for the implementation of public values (fostering modal shift or planning new mobility projects for instance). The success of these policies – the fulfilment of public values – depends on people making use of the tool.