The cases studied for this Handbook show that public authorities have two major approaches related to their objectives when they develop journey planning platforms: on one hand platforms serve as an outlet to publicise public transport information (‘informational platform’), whereas on the other hand platforms can be utilised as tools for the implementation of public policy goals (‘policy-rich platform’).

Key words: informational platforms and policy-rich platforms

Overseeing currently existing journey planning platforms sponsored by public sector entities suggests that there are two major approaches related to the objectives associated to the design and use of these tools. On one hand, we see authorities that hold responsibilities related to public transport provision looking for platforms that serve as an outlet to publicise public transport information. On the other hand, platforms can be utilised as tools for the implementation of public policy goals. These distinct objectives – a first, more simplistic, and a second, with higher complexity – also result in differences in the features of these platforms – the type of information that is made available, the way it is displayed etc., as described below. Empirical observation shows that simple informational platforms (first type) are most common. More complex policy rich platforms (second type) are not common. We will discuss why, but also wonder: why not?

‘Informational Platforms’ are essentially concerned with providing comprehensive and accurate information on transportation options. Information is ideally objective and does not have any bias. They are mostly focused on providing ‘door-to-door’ trip advice with public transportation modes. Their core service is to provide users with public transport timetables and a reliable source of information on how to move from point A to point B. They work as transit information outlets and salient public values are time savings or trip convenience (shorter walking distances or smaller number of transferences between modes) for the individual user.

Public Transport Victoria and Plan a Journey illustrate cases of platforms geared to serve as a source of information to general public on how to move using public transport modes. Both also consider bike trips as an alternative (city shared bikes in London’s case), though these are only included in recommendations after specific input from the platform user. In a similar vein, Stuttgart’s VSS and Helsinki’s Reittiopas offer commuters a planning tool that allows them to move from point A to B in the respective coverage areas using public transportation modes. These two platforms also provide bike travellers with (comprehensive) journey information and, in the case of VSS, ticketing information and purchase option is available online as well. Qixxit, a platform organised as a separate corporation but developed by the German national train company Deutsche Bahn, states advice neutrality as one of their core principles, i.e. to avoid any and all bias in the information it provides. Finally, OV9292 in The Netherlands could also be included as an example in this group. The platform provides journey advice to its users suggesting trips that may involve all public transport options (buses, trains, trams, subway, and ferry). In this case, however, two aspects are worth highlighting: first, rather than being developed by a public body like in the previous examples, OV9292 is a corporate entity owned and run by transport operators, both public and private. Second, according to accounts from users, a mild bias can be identified in the platform: when the final destination point is somewhat near to two public transport stops, the application will recommend the one that makes the trip longer (and therefore more profitable, given the Dutch kilometric fare scheme[1])

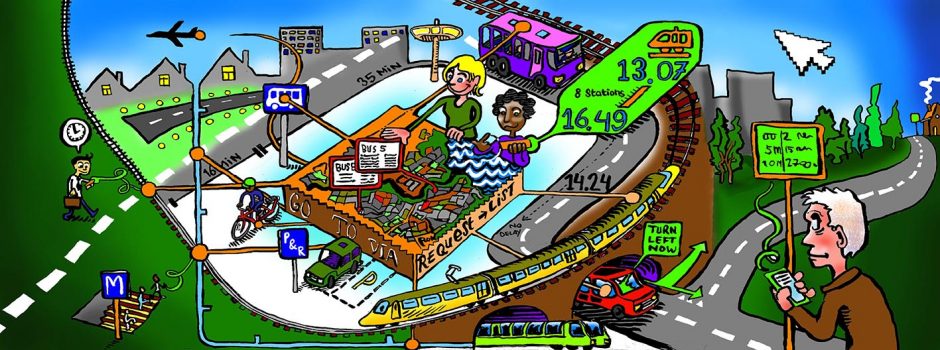

The scenario changes when the public sector envisages mobility platforms as public policy instruments instead of only an information service to be provided to citizens. In these cases the platform takes on a nudging role and influences users’ behaviour. These ‘policy-rich’ platforms emphasize collective rather than individual optimization, evidencing public values such as general time saving through overall traffic reduction, accessibility, green mobility, and public health. Promoting collectively desired behaviours may entail increased sophistication with larger and more diversified information to users: information on more modes of transport (multi-jurisdictional public transport, private and shared bikes, carpooling), information going beyond transit schedules or traffic disturbances, e.g. emissions savings, health gains etc.

Examples of policy rich platforms are less numerous amongst the cases studied. CarFreeAtoZ, in Washington DC metropolitan area, is the most illustrative. It actively incites users to adopt behaviours that are aligned with public policy goals and values such as general welfare to be achieved with traffic reduction, emission cuts, or even health related outcomes. The platform is part of Arlington County’s Transport Demand Management (TDM) strategy and was commissioned by Arlington County Commuter Services – the specialised public agency in charge of TDM in the County, evidencing even more the original intent of promoting certain policy objectives through the platform. CarFreeAtoZ brings schedule information of public transport operators from multiple jurisdictions (Virginia, Washington DC, and Maryland), as well as information on the availability of shared or private bikes. Additionally, it also provides car drivers with information on routes and journey length. The platform also has attempted and is still trying to develop functionalities to facilitate carpooling schemes. Most importantly, for all of these journey options users of CarFreeAtoZ not only receive route recommendations, but also get comparative information about the potential trip choices concerning costs, emissions produced, and calories to be burnt by the traveller. These comparative data is displayed from the onset, once the departure and arrival points are selected by the user. In sum, there is a deliberate support for options that deliver collective gains.

Overseeing currently existing journey planning platforms, the prevalence of ‘informational platforms’ may come as a surprise. Many innovative projects have stressed the potential for journey planning as policy instrument, many have aspired to create policy rich platforms and the technical complexity of these policy rich platforms does not make out a real obstacle. Why aren’t there more policy rich platforms?

A series of factors may influence and constrain the choices of public authorities between building an “Informational Platform” or a “Policy Rich Platform”. Case interviews and literature (e.g. Janssen et al. 2014; Spickermann et al. 2014), indicate some of them: (i) what data is available, (ii) the quality of data, (iii) degree of interoperability of such data, (iv) relationship amongst stakeholders and application of adequate participatory processes, (v) institutional and personnel capacity for data transference and treatment. Thus, the choice will depend on these elements. On a strictly governance perspective, this choice should bear in mind the institutional environment where the platform is landing (From performance to permanence) and also identify and take into account salient public values it wants to implement as well as those from other relevant stakeholders.

[1] Public transport fares in the Netherlands are based on two components: a fixed amount defined by the National Government and a variable kilometre-based fee defined by local transport authorities.