It is tempting to look at the platform as a data repository, with data coming in and data going out after modelling future states of the network and optimised routes. This would mean that governance would for a large part be about data ownership and storage and communication. However, the platform for a large part functions as a portal: data is linked to the platform rather then, transferred to the platform. Or even, the platform only allows for algorithms to be carried out on externa data, that never leaves the servers of the owner of the data outside the platform. Now governance of the data is about use of data that has to be linked by the platform from the data providers to the users, through licences, SLAs and APIs.

Key words: Data, Privacy

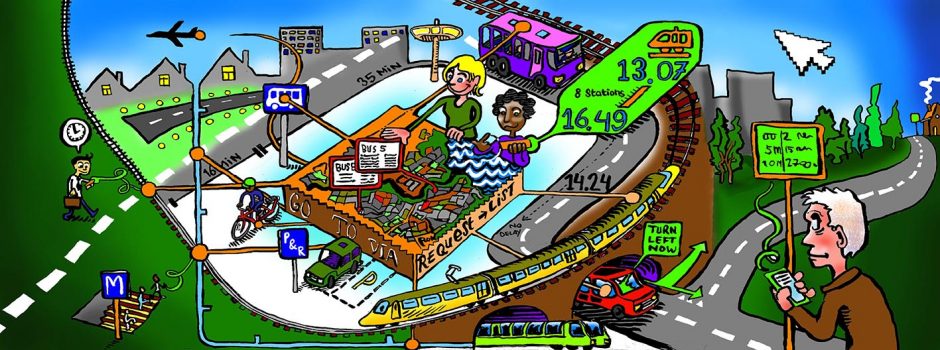

The PETRA platform works on data. For the platform to deliver value to its users, data has to come in, and has to go out, and data has to be retained, possible aggregated. And obviously, that data has to have relevance and quality, relevance for the mobility related questions users might want to answer using that data, quality in the sense that it is a sound representation of real-world situations.

The in and out flux of data is a simplification in the current world. Data coming in could very well be a managed license, managed by the platform for all users of the platform to use the data from elsewhere. Data coming out could very well be an API (application programming interface), that allows users of the platform to interact with the data the platform is moderating. These more dynamic governance models for data transactions obviously fit with the more dynamic forms of mobility data that the platform is often “handling”, like real-time GTFS and traffic counting. No governance of control or ownership of the data by the platform is needed.

Privacy

Oftentimes the platform is helped by using data that is privacy sensitive. For mobility data platforms, the locational characteristics of individual data are key examples of that. For analysis and modelling, the optimum location data of cars or phones is at the individual level. This allows for the combination of individual paths into trips or travel patterns, highly valuable for modelling future behaviour. Modelling tools in the platform are generally helped by higher granularity of data, meaning closer to identifiable individual paths.

Obviously, this raises privacy issues. We have seen several answers in the cases, affecting governance. On the one hand, aggregation into groups of travellers could be done. Individual data is not traceable after aggregation of 100 trips by various travellers (Pisa). This obfuscate the individual trip and make it non-traceable. Obviously, those individuals represented in the data in the platform should feel confident with the such a privacy securing mechanisms, governance should support that confidence.

In another form, individual location data would not be provided to the platform by those owning the data, but the platform would ask those owners of that data to perform transformations on the individual location data set for the platform, only providing the platform with aggregated outcome. This allows for use of individual data for analysis and modelling, without revealing the identities to the analyst and modelers. Again, those represented in the data should feel confident about the obfuscating effect of the transformation. The governance challenge in both is that those represented in the data not experience their provision of data, as can be easily the case with Bluetooth or Wi-Fi tracking. Or if they do willingly accept their representation in the data on the platform, they feel little control over the way in which that data is used and “scrubbed” of their identities. In several countries, privacy regulation has been set up, with watch dogs overseeing the way in which the data is used, limiting more tailor-made governance models.

So, privacy is mainly about limiting the individual traceability of people, mostly from the data from the location services in their phones (like locational coding of pictures), location-based transactions (like checking in in public transport) or locational identification of their cars or phones (like number plate recognition). Locations are a key element, as we are dealing with mobility platforms, but the same could hold true for health and financial data. Sometimes the need for platform specific governance related to privacy is limited, as national regulation exists that providers of individual locational data feel confident about. If not, on the data input to the platform, privacy should be protected. The demonstrators showed governance models that allow for really high quality data for use in modelling within the platform, where the individual traceable data never left the owners systems outside the platform. This al works under the premise of an intricate governance model between data provider and the platform.

The cases also showed that the data on individual paths is developing rapidly. Social media posts often contain a time and location stamp, allowing the constructions of paths based on public data. This goes beyond Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and number plate tracking, as the provider of the data is explicitly and actively disclosing the data and making it public, and it does not need local trackers (camera or sensors). In addition, more and more apps are tracking more precisely the paths of individuals. This will likely make this information wider available at lower prices.

Data in

On the data coming in side of the platform, a number of governance models is apparent. First of all, we see that open data is a governance model. In Haifa, the national government is gathering the schedule data of operators in GTFS and making it available as open data. Also in the Netherlands, 9292OV is playing a role in providing schedule data to users as open data, including real-time data. Use of the open data is in principle free. However, in some cases operators are hesitant to provide real-time data, as it could be used for other purposes. We saw such limitations in Tel Aviv, London, Lyon, and Vienna. Mostly, the objections are about use of the data for performance measurement, without a proper institutional environment. The reactions varied from reluctance to provide real-time “as-operated” GTFS data, to clauses excluding the use of this data for statistical performance analysis.

Obviously, getting this data is helped when the manager of the platform is part of the organization owning the GTFS data. That can be the case if the management of the platform is performed by a public transport operator. However, this is less helpful for the inclusion of the data from other operators. This is also the case if the management of the platform is performed by a public authority buying the transport services from operators, for example through tendering. In that case it seems to take several rounds of contract renewals to align the needs of the platform with the possibilities and willingness of the operators. Or it can be the case that the management of the platform and the operator are part of the same governmental entity. In this case hierarchy plays an important role in realizing the potential of the platform through convincing the operator.

Other important data into any mobility data platform is map data. We saw various models with various consequences for the governance. The platform AnachB in Vienna has developed its services on top of an own GIS system. This means an internal service-level agreement has to be in place to be able to secure the platform services in the long run. On the other hand, though, CarFreeAtoZ uses OpenStreetMap. In between is the broad use of google maps.

For that data to be able to be used in modelling and analysis, the data has to be stored and possibly aggregated. This means that the governance of the system should allow for data ownership and in many cases security.

Above we discussed location and flow data of individuals, schedule and real-time public transport data, and map data. This is the basic data set the platform will need to operate along its original intent: real-time integrated travel plans. The cases showed platforms that provide data for travel planners, but then go beyond. In Lyon and the Netherlands, we saw parking place availability and rent bicycle availability. In Lyon and Haifa, the goal of the platform developing beyond travel planning for end-users. The platforms gather a great deal of mobility data and makes this available for all kinds of users, from traffic control centers and infrastructure planners at government, to any commercial users of the data. The platform has developed from a purposeful combination of data, aimed at making a clever travel planner, to a broad portal for data, to be used by anyone to optimize mobility in the region.

Data out

The shift described above has clear consequences for the governance of the data out. If the aim is to develop a travel planner, this allows for simple governance model: the end-user of the travel planner has a license, which can contain both the conditions for use, as well as possible ways of using the data from the end-user back in the platform. The transaction is clear, with potential gains on both sides and controlled use of the data.

However, when the purpose of the platform is not limited to realize a (real-time) travel planner, or if the travel planner even shifts outside the scope of the platform, an alternative governance model for the use of the data is needed. If the platform is gathering all kind of public data using governmental resources and making that available for internal use within the governmental entity, this can be arranged with straightforward service level agreements. However, if the data is made available more widely, open data becomes a likely alternative. Interestingly, the Lyon case showed how in that case data can be licensed. The choice was made to stimulate the market and innovation by having paid licenses for monopolistic service providers using the data, whereas new entrants would have free licenses.