The intelligent mobility platforms involve a wide range of trade-offs, some explicitly dealt with others hardly mentioned. Though ‘making well-informed trade-offs’ is the key goal of these innovation projects, the developers’ ideas about who should make which trade-offs appear rather premature.

Key words: trade-offs, accountability, utopian thinking, governance arrangements, nudging

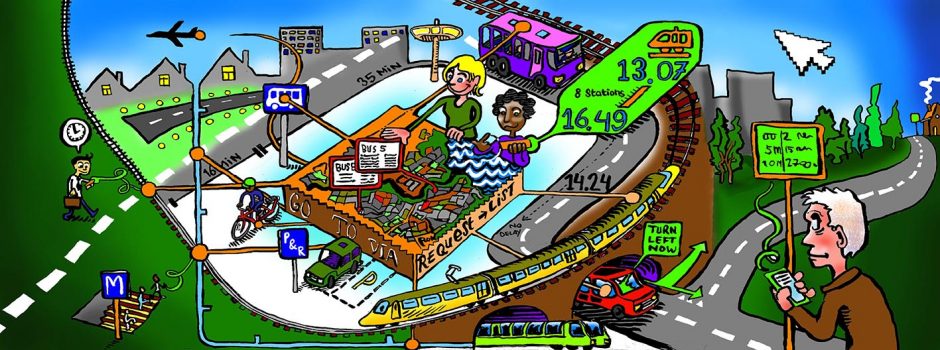

Intelligent mobility platforms generally start as utopia, a paradisiacal new world. Thanks to these platforms, better informed customers choose the greenest, safest and cheapest transport modality and better informed governments make policies to further improve all mobility systems for all goals. But should we perceive these platforms as a paradise without pain? More likely is that they bring trade-offs, gains and pains, given the many competing values and interests in the mobility sector.

How do these platforms deal with the trade-offs they interfere with? What kind of trade-offs? Who makes them? Let us first try to describe the trade-offs made and save our judgment whether to consider these trade-offs good or bad for later.

Many trade-offs pop up in our studies. We encountered two major causes: transport modes and data quality. Encouraging people to use their bicycle, for example, can be positive for health and environment, but it may simultaneously increase the number of accidents, including the number of casualties. Sometimes, safety and sustainability are at the same side of the trade-off, for example in the case of train versus bus (e.g. Digitrans). But when is a safer and greener transport mode preferred over a cheaper and faster one? The other major cause for trade-offs is data quality. Being well-informed is the central premise of why we want these platforms, but data quality may require quite some time and investments and it is never perfect. Making data available also obliges to maintain data. When should bad data quality be a reason not to disclose the data? How should data quality be measured? Collecting data from mobile phones, furthermore, requires battery use. How to balance data quality with efficient battery use? These are the major examples of trade-offs we came across.

Also noticeable are trade-offs that we did expect, but did not really came across. For example, when is the innovation project worth its investment? Or, when is the option to stay where you are better than using any transport mode at all? Or, what if being well-informed at the system level competes with being well-informed at the individual level, like communicating vessels? These three very different trade-offs, though relevant in practice, appear undiscussed by our respondents.

We have two points of discussion with regard to how platforms deal with these trade-offs.

First, the question who should make which trade-offs is answered very differently per case, if not left implicit. Should it be the government, the market, the expert or the individual traveller? If we look at it from a theoretical perspective on governance arrangements – market, hierarchy and network – respondents generally propagate to entrust trade-offs to a single governance arrangement. ‘That is up to the market’ (market) or ‘the government should take the lead’ (hierarchy) are often heard phrases. In practice, however, trade-offs typically come about in a mix of governance arrangements. Nudging, for example, is a frequently used hybrid between the preferences of a so-called ‘choice architect’ (hierarchy) and the preferences of users (market). Yet, we hardly came across arguments how trade-offs should result from a combination of multiple governance arrangements, i.e. market, hierarchy and network. A network arrangement is also hardly argued for as a way to make trade-offs, despite its omnipresence in practice. Respondents tend to have a straightforward idea of how trade-offs (should) occur in the platforms they support, whereas practice remains more fuzzy and less outspoken.

Second, being well-informed is considered the key contribution of these platforms. But what does ‘being well-informed’ exactly mean if it remains implicit precisely where and when trade-offs are and should be made by whom? An answer to this complex question is generally left to the users. An obvious way to get an impression of the information needs is user involvement. A minority of platforms have invested in this. User involvement answers the question what information the users prefer for their purposes. However, for trade-offs to be known, the more advanced question why users use the specific platform should be answered. We haven’t found a platform that invested in this intelligence yet. As a result, the trade-offs about data quality remain somewhat implicit. And the platform that is consciously dealing with trade-offs remain utopian.