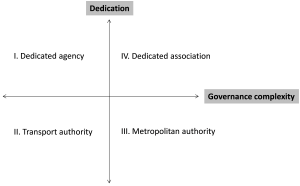

Four general organisational models can be identified relating to the way public sector is set-up for developing mobility data platforms: (i) the dedicated agency, (ii) the transport authority, (iii) the metropolitan authority, (iv) association with transport operators.

Key words: organisational setting, governance modes, transaction cost economics, public values

In another column, this Handbook discusses the dichotomy between private and public initiative platforms. Now we take a step further in the analysis of the latter. In particular, the question we want to discuss is two-fold: what are the governance regimes that can be used to organise journey planning platforms? How should public administration decide on which of them is more suitable? No single answer or ‘one size fits all’ formula exists. The existing range of alternative arrangements can serve policy-makers as an inspiration to customise their product according to their needs and objectives.

Amongst the platforms studied for the preparation of this Handbook, four general organisational models were identified:

- The dedicated Agency

The most illustrative example of this arrangement is CarFreeAtoZ. The platform covering the Washington DC Metropolitan area was commissioned and is managed by the Arlington County Commuters Service (ACCS). Established since 1989, ACCS is the entity within the Transportation Division of the Arlington County Administration that is directly and specifically responsible for taking care of travel demand management initiatives. Therefore, local authorities believed in the need for and adequacy of a separated and dedicated agency to plan and implement specific objectives associated to mobility, such as reduce congestion by fostering carpooling and modal shift. Within this context the platform is clearly part of a policy strategy to incentivise sustainable mobility behaviours that maximise collective gains. All data coming from different transport providers is directed to ACCS that, through the commissioned private developer, fuels the platform.

- The Transport Authority

Examples of transport authorities managing journey planning platforms are numerous – Public Transport Victoria, Reittiopas, and Transport for London illustrate the choice for this governance structure. In the case of the latter, each mode of transport is managed by a different unit within TfL and these units collect the respective mobility data. All this information is passed to a specific unit in the entity that is in charge of Plan a Journey platform – this unit has several tasks: it keeps close link with different departments in TfL to obtain data, organise the information received, treat some of the data to improve their accuracy, and publish the information, managing and maintaining the website. As a unit within TfL, the department’s role – and ultimately Plan a Journey’s aim – is to provide the best information possible to users, without any specific policy objective associated to it.

- The Overarching Metropolitan Authority

Optimod in Lyon is directly managed by the recently created Metropolitan Authority of Lyon – Lyon Métropole (in force since January 2015). The body merges responsibilities that were previously assigned either to the Rhône Department or to the 59 municipal governments that constitute the metropolitan authority. One of the main roles of this authority is to take care of the planning and investment in mobility. This task is done with the support of a transport authority – Sytral – that manages bus, subway and tram in Lyon. The mobility data is gathered by the operator of these modes (private company competitively selected in tender procedure, currently Keolis), later transferred to Sytral (as per contractual obligation), who then passes them to Lyon Métropole. Lyon Métropole also uses data from other sources with respect to modes that are not public transport – from the traffic control centre (CRITER), for instance. The metropolitan authority owns Optimod and developed the platform made available to users.

- Dedicated association between Authority and Transport Operators

9292OV and VSS are two examples in which both public authorities and transport operators (public and private) are associated to develop a journey planning platform. In these cases, some degree of governance complexity emerges due to the varied source of funding for the platform (public and private) as well as the varied range of stakeholders involved and their multiple goals (e.g. provide accurate and objective information, promote the use of public transport etc.). In addition, these different stakeholders also accumulate different roles – in both examples the transport operators accumulate dual roles: first as platform sponsors, and second as data providers. Due to all these factors, in principle, this associative arrangement may require more sophisticated decision-making mechanisms – the more numerous and varied stakeholders and respective interests are, more complex coordination becomes, as discussed elsewhere in this Handbook (Mapping stakeholders in mobility platforms and their interests).

Overseeing the organisational models identified, we can summarize their differences in two main dimensions. On one hand, they differ in their dedication towards the platform. On the other hand, they differ in the governance complexity their model brings. Both the Metropolitan authority and the dedicated association imply significantly more governance complexity in their models. This is summarised in the figure below.

Figure 2: public organisations for information platforms: 4 models

The governance model to organise the development and management of a mobility platform within public administration may assume varied forms. More centralised and generic governance arrangements or models that pursue less integral and more dedicated structures have each their relative merits, as economic theory on governance of organisations tells us. Assessing the trade-offs involved in each governance choice requires looking at characteristics of the different tasks and stakeholders working to keep the platform up (information ownership and flows for instance). However, the most suitable alignment between governance mode and the transactions and interactions necessary to develop and maintain a mobility platform go beyond the purpose of maximising and optimising results in each trade-off. The successful choice must rely essentially on the public values that are sought and being put forward.