In theory centrality results in integrality, but in practice integral decision making on that same central level may be harder to accomplish than on a decentral level.

Key words: centralization, funding, integrality, specialization, institutional levels

Just two questions. Who pays? Who profits? Ok, a third question. Are those who pay the ones who profit? These may be bold questions, but they are of course highly relevant for the realization of smart city projects. Motives for making cities smarter are usually problems that are perceived and experienced right there: on the streets, in the cars, in the buses, etc. Streets get congested, air gets polluted. The authorities close to the problems are looking for solutions. Many smart mobility projects are organized in the context of ‘smart cities’. Rome, Haifa, Venice, Helsinki, Melbourne, Lyon are all made smarter. The cities and their residents profit.

However, these projects are funded differently. In Helsinki, Lyon and Rome, for example, local funds are important, whereas the projects in Haifa and Melbourne are mainly funded by central governments, at a much higher level than of the cities. There are many more local projects that require funds, all with good arguments. And – it’s life – there are more good projects than there is funding.

This links to a classic dilemma in organization theory: should decision making, in this case about funding, be centralized or decentralized? Main arguments for decentralization is that knowledge and expertise is generally situated on a decentral level. Decentralized decision making then has the advantage that decision makers actually know what they are deciding upon. They need less reports, forms and other standards. Instead, they directly talk to the people that matter and experience the problem to be solved themselves. However, there is a downside. Decentralized organization may also lead to unfair differences between decentral units and missed economies of scale. Some cities are in more need to get smarter than others. Central authorities have that helicopter view and may facilitate a fair and efficient allocation of money.

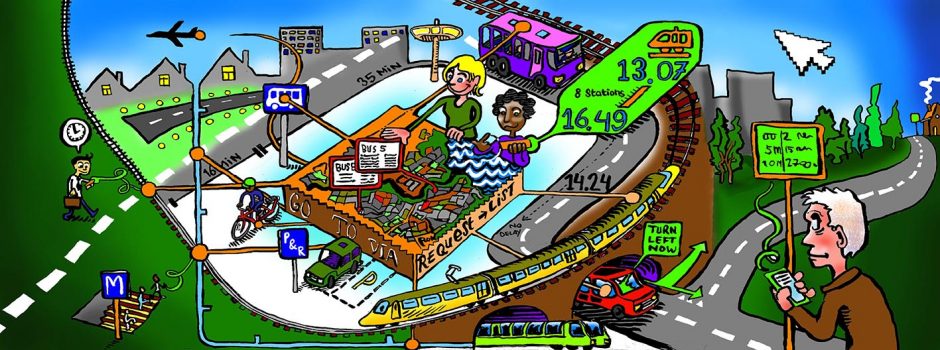

This means that centralization serves integrality. This is much needed in smart city projects. Smart mobility systems require much integration, especially of policy fields. The policy field of transport and mobility is central, of course. But smart mobility is also about tourism, about information and communication technology, health and environment. All policy fields call for attention. A smart mobility system is able to respond to those calls and integrate their issues into a device that aims for the virtues of centralization.

However, we found that centrality also blocks integrality.

First, it may not be a coincidence that we meet the less developed and less ambitious data platforms in the centralized cases, such as Melbourne and Haifa. This is perhaps explained by the fact that central decision makers rarely taste the air of the city in question, or get caught in the traffic jam. The urgency of getting smarter is felt much less at authorities on a larger geographical scale. A second reason is an organizational issue. As stated, integration requires coordination between multiple policy sectors, such as mobility, environment, health, and tourism. The smaller an organization is, the easier this coordination gets realized. For instance, it is easier to talk to other people of other departments because of shorter distances, and people tend to know each other. For this reason coordination, sometimes doesn’t need to be formalized. Authorities on a decentral level tend to be smaller than on a central level. The larger the funding and managing authority, the more likely they have to specialize their departments. They are hosted in separate buildings, have different ict-systems, and develop separate procedures. This requires much more coordination. More importantly, the separation of departments gets a segregating force. Specialized departments require smart mobility applications to get specialized as well, and they need to be labelled as ‘mobility project’ – for the mobility department – or ‘sustainability project’ – for the department of health and environment – etcetera. A project that is integral at its core will have a hard time to get funded, because it cannot be framed along the lines of organizational departments. The project is integral, the departments are not.

The centrality paradox of smart mobility is that in theory centrality results in integrality, but in practice integral decision making on that same central level may be harder to accomplish than on a decentral level. Both levels contribute to integrality, but may compromise the integrality of the other.

Another way to put this is to say ‘what’s the right level – or scale – is actually not a relevant question. Moreover, for most emerging smart mobility projects the relevant levels of decision making are a given. The reasons behind that those levels has its roots in history and serendipity. However, when people in future talk about history, they are also talking about here and now. If the levels are a given for a specific project, that doesn’t mean these levels will not change. The centrality paradox, in fact, provides a constant rationale for adapting the scale of the project on behalf of integrality, as was the case in Lyon and Vienna. Whereas these scale changes may often appear to have a conscious component seemingly as part of an endless struggle for power, the centrality paradox offers a substituent explanation why consensus on ‘the right level’ is never reached.