The foundation of a platform takes lots of time and effort. It would be efficient if they will function for a long time, at least survive the implementation phase. This ‘permanence’ is likely to correlate with performance: the better the performance, the more viable the platform. However, this relation is not that straightforward as it seems.

Key words: launch, implementation, performance, institutions, private platforms

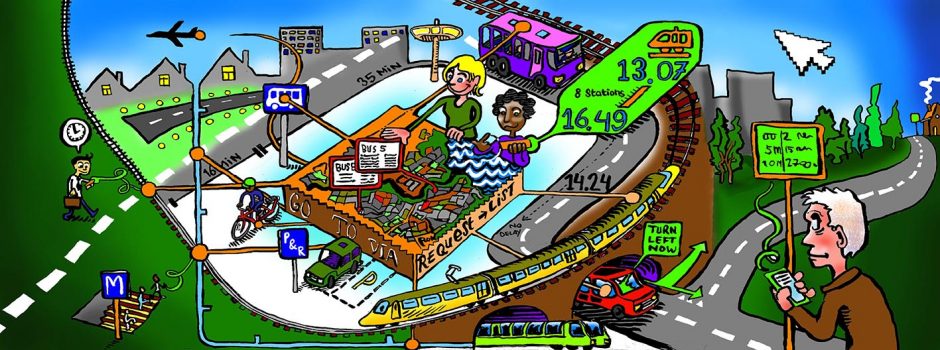

Once, a more or less developed smart mobility platform hopes to get implemented. A critical moment and no sinecure. Platforms must convince a critical amount of people – including users spending money or time – to have added value. But launching a platform is just one moment in time. It may be an instant gratification peak after which everyone goes back to normal. The first years after takeoff are critical as well. In this period, the platform needs to institutionalize. Using it should wear down as a new routine and fit the existing culture and rules relevant in a certain area.

An often quoted design principle is to treat most of the ‘institutional landscape’ as a given, since it is hard to change in the short run. Many great ideas eventually strand because the world proves less makeable than thought. When we take the warning seriously, when culture, rules and habits matter and are hard to change, at least in the short run, this may have major implications for the implementation of smart mobility on the longer run. During the launch of a platform, what may look like a rather straightforward implementation process, may over many years actually prove to be a mutual adaptation process between the evolving new features of the system and the rigorous institutional landscape in which they will have to function. As a consequence, performance on the short run may neither be a guarantee nor a reliable indicator for survival.

Overseeing the studied platforms, what may indicate that eventual performance proves to be a false lead? What may cause well-performing systems to dissolve in obscurity?

As we have seen in the Superhub projects in Milano and Barcelona, for example, there is a risk that the features of the system – cutting edge and expensive as they are – will be rejected by powerful actors, such as governments funding projects, authorities managing systems, and users preferring platforms developed by competitors. This is not just about performance, but also about political priorities, ambition levels and the willingness for organizations to pay its management costs. The Superhub-initiatives in Milano and Barcelona were funded by the EU, but couldn’t find enough political support in the cities they are implemented once funding stopped. As a result, they became orphans. They are now framed as ‘experiments’ by the engineers that developed them.

Projects developed by an institution in the regions themselves – such as in Lyon, and the Vienna Region – are less vulnerable to this risk. A dedicated problem owner – such as transport authorities, or a joint venture of transporters backed by public authorities in the Netherlands and Stuttgart – helps to overcome any time of doubt. They might continue the project if the amount of users doesn’t meet expectations yet or if technical problems arise. They have already invested in the system or in the cooperation with other actors to a certain extent, making them willing to continue even if performance is not ideal.

Another example is the Dutch 9292.nl, in terms of use a very successful and long-lasting service. It is used by many people and the very name of it, based on a meanwhile old fashioned phone number, has become an institution itself. But the quality of service may neither be called bad nor outstanding. Dutch people can complain about the website being down, like they complain about the weather. Moreover, it is not at all ambitious or cutting edge – i.e. only encompassing public transport time table data. Perhaps the popularity in use is not despite but thanks to a lower ambition level.

Summing up, we meet two risks for well-performing, publicly funded platforms to dissolve in obscurity: high ambition level and lack of congruence between leading developers and dedicated problem owners.

Risks for privately funded platforms are somewhat different. Commercial parties such as MAAS and Ubigo offer a concept and a platform to their clients. In doing so, they may reduce the transaction costs of authorities to develop smart mobility. These commercial parties spread their risks. The more clients they have, the less they have to rely on a single project. The evaluation of performance is up to the clients. Are they satisfied with the service? This may depend on the performance itself, but also the client’s transaction costs compared to its – unknown – alternative. Moreover, there might be issues. The implementation of MAAS in Helsinki has been slowed down by uncertainties about the position MAAS is going to take in between the public transport providers. MAAS is a new kind of actor and transport providers perceived that they might give away customer access and relationships. Cooperation with MAAS implies uncertainties about the position of public transport and also the government promoting public transport. The amount of willingness to do this and the willingness to trust market parties such as MAAS may depend per country, region or city. And it is relatively independent from performance.