…from the dynamics of governance to the governance of dynamics

Governance may frustrate the designability of journey-planning platforms. Essential for a design team is to couple three core qualities: knowledge, authority and problem ownership. Dynamics may frustrate the design team in doing so. Different complex-adaptive strategies can be chosen to deal with this.

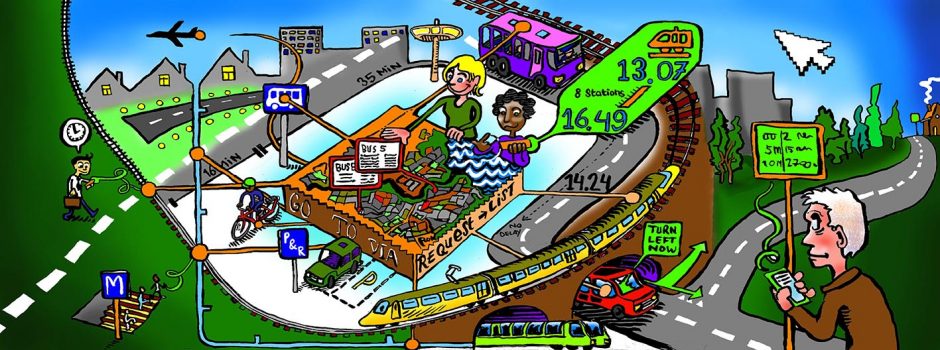

From a design perspective, journey-planning platforms are developed by a design team on the basis of a fixed program of requirements and implemented accordingly. From a governance perspective, it is less simple, since it involves not one design team but multiple stakeholders. Accordingly, governance is not only the subject of design, but the design process is also subject to governance. The dynamics of governance, as described in this handbook, therefore may challenge the design-ability of journey-planning platforms.

Governance is about the interaction between those providing information, those integrating it, those using information, and all others that have desires concerning the platform. For PETRA – just as many other platforms – government is involved, because they feel public values are at stake. This means that governance must bring together different positions and interests and will also cross the public and private divide. This complicates the transactions between the actors involved. Will government’s will prevail, like in a hierarchy? Are relations better described as market transactions? Or is platform development and management better understood by the broader concept of networks, involving multiple actors that are mutually dependent? The obvious answer is that governance in practice show a mixture.

The design team is confronted with this governance mix and has to find a position in this socio-technical world of intelligent mobility. It involves designing a technological feature that has to satisfy these actors, and at the same time a context that facilitates actors to organize themselves – for instance by contracts or organizational structures. Designing also involves adjusting the design in a socio-technical context, for instance the culture, habits, and the regulations of the place where the platform has to function. It is easy to end up in despair. If platforms are subject to diverging interests, if objective knowledge is scarce and even norms of what is right diverge, is intelligent mobility governable at all? True, it is easy to ask questions with no easy answers, but after all, this is exactly what makes designing such a complex activity. Despite these governance difficulties, our empirical work shows some starting points for design.

We found three qualities of actors vital for the governance of intelligent mobility platforms. We believe that each of these qualities can manifest themselves as necessary condition for success:

- Knowledge. What actors have scarce information and knowledge that is critical to developing the platform? These actors have vital ‘can do’ qualities.

- Authority. Another obvious ‘can do’- quality is the ability to impose their definitions and procedures on others.

- Problem ownership. Where the former two factors represent power qualities, a third factor is about ‘will do’. What actors have the drive to solve problems as they emerge, for instance by taking the lead in mediation among actors or connecting knowledge fields?

These three qualities are usually distributed over more actors. In this context we defined four models for mobility platforms. The models are based on the extent to which a platform owner is dedicated to infomobility and the organizational complexity of the platform owners. The governance of mobility platforms seems to be powerful if the three qualities are unified in one actor – such as in a dedicated transport authority – or coupled in a strong arrangement among multiple actors to overcome the organizational complexity.

This surely doesn’t mean that there is a perfect model. Development and management of platforms seems to be too dynamic for a perfect model. We found a range of different dynamics relevant to the success of keeping these three qualities together.

- A first dynamic is about authority. Although many platforms are developed on a decentralized level, close to the knowledge of the region and the problems experienced, at times authority or funding is needed from a central level, invoking centralizing forces.

- Second, it seems hard to pinpoint a perfect geographical scale. Problems – such as congestion – may manifest across administrative borders. The more borders crossed, the more entities needed for coordination, the more compromises an administration has to make.

- Third, a good platform may attract interested parties outside the region, adding desires and complexities.

- Fourth, because platforms require diverse disciplines that are usually organized in specialized departments – i.e. ICT, environment, safety, mobility – the emphasis of the platform may change, largely depending on what department is in charge of the project.

- Fifth, and related, the platform’s life path from cradle to grave doesn’t go straight. Implementation and management are vital processes that may deviate significantly from the designer’s plans.

These dynamics make perfection just a temporary delight. Indeed, a perfect choice now may be a curse in future because of path dependencies. As an alternative we would call designers to find a way to deal with the dynamics of infomobility platforms. Instead of perfect, a governance model should be adaptive. Roughly, two directions of thought on adaptive governance can be distinguished.

A first direction is anticipation. The need for authority, need for funding, possible spinning wheel effect, implementation issues, specialization, implementation issues, they all should be considered beforehand while designing a platform. This is of course a huge task, however this handbook provides a broad agenda for issues to be tackled.

A second direction is resilience. This assumes the occurrence of unexpected dynamics. If uncertainty is taken as a given, anticipation will by definition fall short. Recommendations then will target the organizations and transaction devices to be flexible enough to cope with dynamics. For instance, arrangements for entry and exit, feedback and conflict resolution mechanisms should be in place. However, these arrangements are just paper. Basically, the ultimate resilience mechanism is trust. Trust is hard to design for. It is a prerequisite for overcoming differences in times of technological and social turbulence.