There are good reasons to engage travellers in the development of journey-planning platforms, but few platforms do it. Recognizing this paradox as a dilemma is a first step to change the status quo (if you want to).

Ask someone about what is necessary for the development of a journey-planning platform. The majority of answers will name three essential roles.

- a platform owner

- a technology developer

- a data provider

As we have seen, these three roles can be filled in by a variety of actors. The platform owner can be a governmental entity or a private player. The technology developer can be a separate tech company holding technical expertise necessary to build the artefact, but it might also be done inside the same organization that owns the platform or provides transport. The providers of data may involve many different actors. It might again be the same player taking the owner role or a third party, like a transport operator or a telecommunications company for instance.

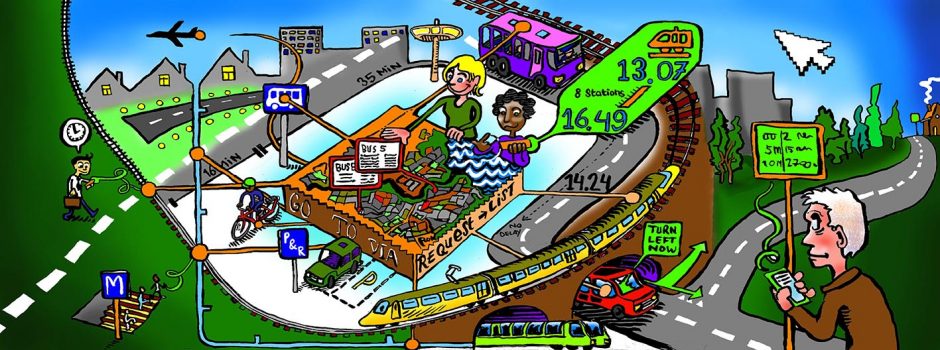

Although this group of roles and actors may look comprehensive, a fundamental aspect is missing: the user. This ‘route’ is about the traveller and the different roles he or she may take. Another ‘route’ on policy instruments will focus on the government as user of these platforms.

The interviews conducted for the preparation of this Handbook confirm this gap: travellers are only thought of as the platforms end-users, and their role as part of the development process is not recognised. Stating adamantly that this approach is inadequate is too daring – in public policy there are no universal recipes for success. Nonetheless, at least three reasons justify to re-consider this predominant view and to acknowledge the importance of involving travellers in the development process of journey-planning platforms.

- Allowing all stakeholders, including travellers, to have a say in decision-making processes is conducive to a more legitimate outcome, therefore enhancing the possibilities of successful – or at least less controversial – design and implementation choices.

- Travellers hold local knowledge – this knowledge, associated to the expected technical and strategic expertise of the platform owner and developer, allows for an improved final product, a better platform.

- As the end-users, travellers are the ultimate target of journey-planning platforms. Whatever the purpose of developing the platform is – be it public policy implementation or profit for the owner – it depends on attracting travellers and making sure they use the platform. Travellers’ expectations and values must be embedded in the product.

Hence, this makes engaging travellers in the ‘development team’ a potentially beneficial strategy.

Throughout this Handbook, a route through the empirical columns discussed evidence encountered in existing platforms in relation to travellers, the roles they assume (or do not assume) in journey-planning tools, as well as reflections on some of the reasons and repercussions of these choices, including consequences for the operationalization of public values through the platform. A possible route to follow this discussion starts with the identification of stakeholders that are involved with journey-planning platforms and some reflections on the usefulness of trying to map them. “Where did all the conflicts go? The sense and nonsense of mapping stakeholders” discusses what is apparently a simple task (identifying stakeholders) and how it unfolds complexities involved in the development of journey-planning platforms: the network of stakeholders, roles and relationships and dependencies between them, their interests, resources as well as potential conflicts of interests that will have to be dealt with.

With this overview as a starting point, the trip continues with a discussion of the potential need for the involvement of travellers in the development process and some of the reflexes of this choice. “Doomed to fail? The need for user involvement” reflects on levels of potential or existing examples of travellers’ participation or use of these platforms. This reflection will lead readers to the next journey leg, with two columns discussing a relevant issue that lays in the background of the choice around what travellers’ involvement ought to be: the value(s) sought with the creation of a journey-planning tool. Whose values will be sought? How important are travellers’ values? And finally, how are these values operationalized? Some of the answers to these dilemmas are examined in “End-users and identification with the public values driving the platform” and “The Frankenstein-trap: proper operationalization of public values”. The same discussion can be approached from an even more practical point of view. What kind of information does a traveller require when planning the trip? How does the information need change during the trip when the traveller is already on-board a vehicle? What kind of features should a platform offer in these cases? By considering the different journey stages a traveller goes through during his/her trip, the next column in the Travellers’ Route – “Tell me what you need and I will (try to) give you what you want: addressing the travellers’ needs” – offers a different perspective on ways to identify the values expected by travellers and also the ways by which these values are put in practice.

| 7 tips to involve travellers in the development of journey-planning platforms |

| · Start experimenting with it, in a minimal way at least. There are many options available. Organize for continuous feedback by travellers. Give travellers a say in the design team. Learning from such experience would be very welcome for current platforms in the making.

· Think in terms of journey stages. The users’ interests are more diverse than often thought. It is not only about travel planning, but also about changing plans or improvising during a trip or even afterwards, to evaluate the trip and the planning experience. · Align the users’ interests with the public values driving the platform. The more alignment, the more travellers may identify with the platform goals. Travellers’ involvement is driven by this identification and sense of problem ownership. · Organize for feedback on the operationalization of public values. Organize for dialogue and publicness to test and scrutinize the choices made during platform development. Allow the driving ideas about public values to change. Travellers can be of added value in this process. Use travellers as indicators for success. The costs and gains of journey-planning platforms are hard to assess during their development. Involving travellers can be of added value in this. · Address travellers with a variety of incentives. Don’t treat travellers merely as ‘guinea pigs’ or ‘rational calculators’. The behavioural logic of travellers is anything but simple and consistent. · Draw on creative incentives based on a sense of community and loyalty schemes. Particularly if the public transport provider is the main platform owner, many relatively free bonuses are thinkable, such as extra kilometres or discounts for trips in off-peak hours. |

There are reasons enough as well as options enough to involve the traveller. But why is it not done? It is somewhat of a paradox. Of course, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Involving travellers means transaction costs, imagine for example if a worldwide journey-planner is concerned. Involving travellers may also make the development more complex. These costs are not only and directly financial, but involve for instance, all the work and time spent to reach-out to a wide number of people and to collect their inputs or to develop a comprehensive decision process. Overall, the option not to involve travellers may represent a less complex and more manageable path. The advantages of involving travellers are less concrete and come later than the costs. Indeed, it is important to assess trade-offs and costs involved in the context of journey-planning platforms. Travellers, public authorities, developers, transport operators all have different interests, different needs and conciliating these sometimes conflicting perspectives implies trade-offs. Important questions emerge: What kind of choices and trade-offs are made? Who is supposed to decide on these? How are travellers being benefited? At the end of the Travellers’ Route, “Pain in paradise: accounting for trade-offs; assessing right now: gains, costs and the traveller’s logic” addresses these matters.

Involving travellers imposes a dilemma for the developers of journey-planning platforms with short term costs whilst gains are less concrete and come in the longer term. A schematic dilemma box below shows it.

| + | – | |

| Involving travellers | · More insight in users’ interests

· More alignment between public values and user’s interests |

· More complex

· More transaction costs |

| Not involving travellers | · More manageable

· Less transaction costs |

· Less insight in users’ interests

· Less alignment between public values and user’s interests |