Governments are special actors, with public authority. They may use instruments that other actors lack. Altogether governments have an impressive toolkit, including laws, regulations, financial instruments and a range of soft behavioural instruments.

Key words: policy, instruments, nudging, law

From the perspective of journey-planning platforms, the government’s toolkit is promising. It is full of possible instruments that governments may use to influence the behaviour of actors. Many public policy scholars proposed typologies to oversee these policy instruments public authorities may use. The book ‘Carrots, sticks and sermons’ edited by Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung (1998), for example, discusses and critiques many attempts that try to do so. The book title quite catches the lion’s share. Carrots stand for financial, sticks for legal and sermons for communicative instruments. A general problem with more advanced typologies and their terminologies is that they are often culturally biased and they easily age and get old-fashioned. Still, we can identify a few recurring and relevant dimensions or distinctions across major typologies. We will discuss them.

First dimension is the distinction between tools for detection and tools for effecting (Hood, 1983: 3). The two terms come from cybernetics. Carrots, sticks and sermons are all instruments that aim effects. Besides that, policy instruments may also aim to detect, to gather information and explore a possible problem situation.

A second often-used distinction is that between imperative and voluntary. A legal instrument is often used in a more imperative sense and communicative instruments more in a voluntary sense, but this is relative. Compliance with the law is never strictly imperative, but always goes with some kind of voluntary element and some communicative instruments can be very imperative.

A third major distinction is that between substantive and procedural policy instruments. Substantive policy instruments are more direct in the sense that they are about providing goods to people, taxing people or rewarding certain behaviour. Procedural policy instruments are more indirect. They are about starting a reform process, creating a treaty with stakeholders, adapting the institutional landscape within a sector, etc.

This toolkit is also subject to change. Some tools are deemed old-fashioned, others are found full of promises. Especially soft behavioural instruments are in vogue currently. Governments have a variety of means – i.e. budget, authority – to influence the behaviour of actors by communication. In popular language, they may nudge actors to behave more in line with a public goal.

Thaler and Sunstein (2008) wrote a standard book on nudging. In theory, nudging is seen as a way to improve the world by tinkering with the choice architecture of the mass. Governments may stimulate people to make certain choices that are considered safer, healthier, cheaper or more sustainable. Thaler and Sunstein specify roughly three ways of nudging. The most obvious one is direct incentives for people to make certain choices. A second way of nudging is providing information about choice alternatives. A third way is to tailor the process of making choices, for example by implicitly offering a default or by simplifying the process of making choice in a certain way. Simply put, if you offer strawberry and banana, few people choose chocolate. Nudging is a very relevant type of policy instrument for the potential of smart mobility platforms, but certainly not the only one.

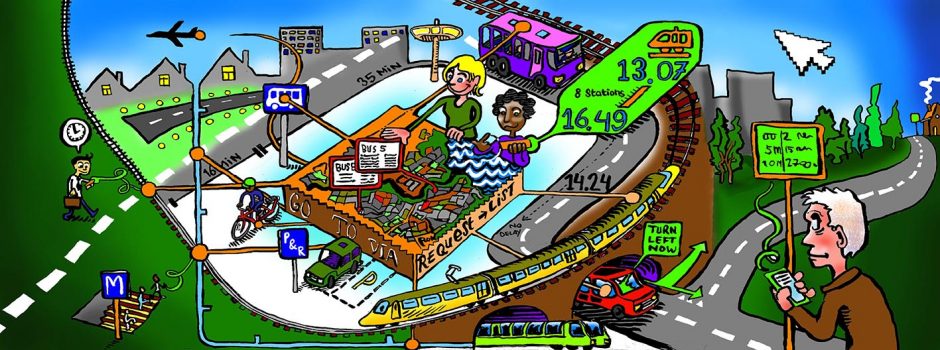

What does this variety and adaptiveness of tools mean for public authorities developing smart mobility platforms? First, smart mobility platforms themselves are promising instruments for public policy. By means of a platform public authorities may try to influence travel behaviour. Second, there are several instruments accompanying a platform. For instance, authority and communication are used to stimulate actors delivering data. Third, instruments also affect actors developing platforms. For example, they may stimulate to improve data management systems for privacy reasons. This column shows, there is a large variety in how to target and design instruments. Not only can these platforms target for a large variety of instruments. Many different types of instruments can be applied at the same time, making a ‘policy mix’.

One note about government is vital here: a full and adaptive governmental toolkit may look promising. However, this must not lead to the perception that governments can use them without any limits. Effectiveness of the tools will be a function of the power position of public authorities, among other actors. In other words: governance also matters here. For instance, communicative instruments may be very imperative if they are backed by hierarchical authority. In a networked relation, imperative communication is less likely to be effective.

The handbook serves to oversee the variety of tools in relation to governance and line up its practical implications.