These three changes rely on technical solutions, gathering and linking new available data sources, new ways of aggregating that raw data into a sound representation of trips made and capacity provided, new ways of modelling travel with the added complexity of making it multi-modal, new ways of modelling how contextual aspects like the weather or nudges drive travel behaviour and capacity, etc. However, they also ask for new governance models or governance blocks to help make them work.

First of all, governance has to deal with the data-in part of the platform. Part of the data comes from individuals and provides details on their locational history, their travel. Under what conditions are they willing to provide them? Is there a privacy issue? How does that align with what is needed? How detailed can we get public transport schedule data and real-time operational data? Are operators willing to provide that to a platform managing organisation, to whom they might or might not have a current relation within the governance system? All kinds of governmental agencies, even private actors, generate data related to mobility demand and supply. Under what conditions does it make sense to make these available in the platform? Only if they can allow for better travel planning or also for more unexpected uses? Moreover, the data that is coming into the platform might very well just be a link. The platform is not a necessarily a repository of mobility related data, but rather a portal. This means that all conditions under which the data is coming in, will have consequences for the use of the data, consequences that are secured in the governance: in laws, contracts, procedures.

Second, the data is processed in the platform. Raw location data needs to be developed into individual trips and travel patterns of individuals and groups. That historic data needs to be combined with all kinds of contextual data to better understand the relation between travel patterns and the weather, events, etc. That historic data also can be combined with sensors, to better understand the effect of mobility on emissions and health. And now that understanding of context and effect of mobility can be modelled into future states of the network and translated to optimized travel plans, not optimized for the individual travel speed, but balanced for collective travel speed and reduced health risks.

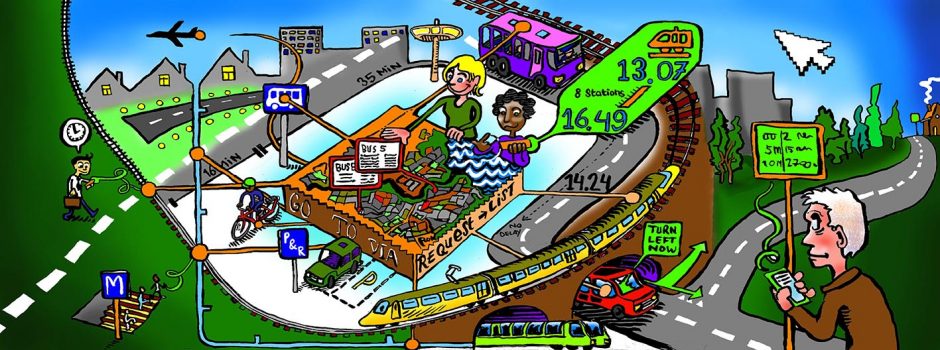

Third, the platform is used to provide better predictions for travellers, that lead travellers to behaviour more in line with the collective needs of the city. The goal is to change behaviour of people travelling through the city for the better, meaning, to align with those collective needs. This asks for governance that ties the end-user to that collective. Planning a trip brings in the collective effects of that trip and lets the end-user decide from that wider context, what we call collectivization. Nudging can be used to let the end-user feel direct benefit from his more collective choice. Also that nudging needs governance. In addition, the city can be helped by the easy availability of a wide data set, either in its raw data availability or in its more processed versions, for example for public transport service planning, infrastructure planning, police service support, traffic control support, etc. Moreover, the data could be used by external parties to provide services to the inhabitants, visitors or businesses of the city. We call this third element, nudged travel planning and data distribution for collective benefits the data-out side of the platform.

The optimal design choices on technology and governance depend highly on the perspective. When the manager of the implementation of the platform is an ICT department of a metropolitan authority, the perspective is different from that of a municipal public transport operator in the metropolitan area, is again different from a mobility policy oriented department of the largest municipality in the metropolitan area. The ICT department is probably more interested in gathering the data and allowing users to use it in a form that creates some value to the city. The operator will likely let the platform drive nudging of people towards public transport. The mobility department will probably try to align behaviour with the policy goals set in the latest white paper. In addition, regional views are probably different from local views, public and private views differ, service provider and service consumer perspectives are not the same, data contributors and data users have different perspectives, etc. As might be clear, there is no single optimal implementation. Governance will have to tie these different perspectives together, aligned with the goals set.

Other questions