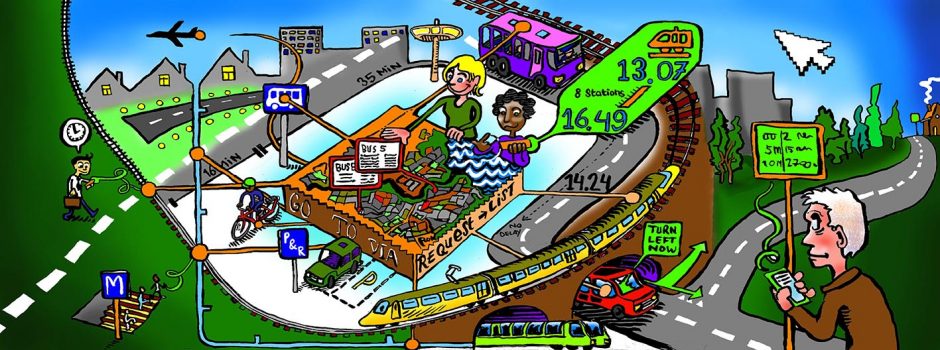

Public authorities interested in developing mobility data platforms, or broader infomobility systems, are faced with multiple challenges that go beyond the technological design of these tools. Different actors affect or are affected by these tools – the authority itself, travellers, transport operators etc. – and they all have distinct values, interests and expectations with regards to the features, functions and benefits of journey-planners. The governance dimension of journey-planning platforms is a wicked problem: tailoring adequate governance arrangements involves issues that cut across different disciplines and involve multiple and conflicting values.

Key words: wicked problems, competing values, uncertainty

In the prologue, we have identified the logic of governments getting involved in mobility data platforms. Governments often are expected to secure public values – such as safety, public health and sustainability. This isn’t an easy task, because these values sometimes compete with each other (Veeneman et al. 2009). For example: a safe solution isn’t always a sustainable or cheap solution. The way these values are traded off and who decides on these trade-offs is often the subject of controversy. The government’s stake in mobility data platforms is subject to multiple values, and consensus on which value should prevail is not always a given.

Several questions illustrate these complex governance issues when developing a mobility data platform with a journey planner: are journey-planners a service supposed to be provided by public authorities to its citizens or should it just be left as a product to be developed by market initiative? Who are (all) stakeholders affecting and affected by the platform and hence that should/could have a say in decision processes? What is the source and flow of the information displayed in these platforms? How is this flow regulated? Are there privacy issues to be considered? How to regulate them? Should platforms be liable for the information they provide? Can a mobility data platform be a tool for policy planning and implementation? If so, what should be the policy objectives embedded in such tool?

In sum, governments involved in mobility data platforms with a possible journey planner often face so-called ‘wicked problems’. A wicked problem (or wicked issue) is the problem associated to a policy question that poses difficulties to authorities and planners due to the fact that it normally cuts across several disciplines and involves multiple stakeholders with varied (sometimes conflicting) interests. Not only that, but also given the presence of multiple interacting players with varying views, the task of agreeing on the delimitation and definition of what constitutes the problem may not be a straight forward one (Bevir 2012; de Bruijn & ten Heuvelhof 2000).

The expression ‘wicked problem’ was coined by Horst Rittel, and later further elaborated by Rittel and Webber (1973) to distinguish between the societal problems that planners normally deal with on one side, and those problems associated to natural sciences on the other. Up to then the paradigm of efficiency guided decision-making and solutions-search but that did not seem to be enough to deal with all problems. Rittel and Webber claimed this paradigm was not representative of all multiple values sought by different affected stakeholders, especially in social matters. Moreover, the wickedness of these problems would go beyond the discussion and search for solutions, but, as indicated above, it is also connected to the delimitation of the problem itself: “As distinguished from problems in the natural sciences, which are definable and separable and may have solutions that are findable, the problems of governmental planning — and especially those of social or policy planning — are ill-defined; and they rely upon elusive political judgment for resolution. (Not “solution”. Social problems are never solved. At best they are only re-solved–over and over again.)” (Rittel & Webber 1973, p.160).

Still according to the authors, wicked problems have at least ten characteristics that help clarify the concept:

- There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem: understanding the problem requires and depends on the idea one has on how to solve it. Problem formulation and resolution are concomitant and shape each other.

- Wicked problems have no stopping rule: the process of dealing with a wicked problem by understanding it, and attempting measures to tackle it has no clear end point. Because the process will continue until the planner decides it is enough and this may be the result of different subjective factors.

- Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad: personal values affect the assessment of solutions to wicked problems. Due to this very subjective character there is no clear definition of what or how things ought to be.

- There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem: every solution to a wicked problem carries specific and potentially unknown consequences, that may also create new unexpected problems.

- Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”: since every solution is consequential there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts and leaves marks.

- Wicked problems do not have an enumerable (or an exhaustively describable) set of potential solutions, nor is there a well-described set of permissible operations that may be incorporated into the plan: there is no way to ascertain whether there is any and what would be possible solutions to wicked problems.

- Every wicked problem is essentially unique: wicked problems always bring a particular feature that turns them into a unique problem and hence without previously tested responses.

- Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem: the causes of a problem may be multiple. Tackling the cause of a problem may also unleash new problems.

- The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution: explanations and reasons of existing problems are multiple and each may call for a different approach to tackle such problem. There is no way to establish which, if any, is the ‘right’ one to be tackled.

- The planner has no right to be wrong: since every attempt to improve a given wicked issue has consequences, people will be affected in some manner whilst the planner will have to bear responsibility for his or her acts.

What does this mean for public authorities interested in developing a mobility data platform or in taking any other role in it? The central argument of this Handbook is that planners must acknowledge that to develop a platform challenges go way beyond the task of collecting data and developing the technological artefact that yields trip advice based on such data. The governance dimension of mobility data platforms is crucial – appropriate governance arrangements must be tailored in order to allow the technological tool to be designed, implemented and also to deliver the expected benefits. On a high-level perspective, this entails policy efforts that coordinate and integrate measures and activities of different governmental and non-governmental entities, a ‘joined-up’ approach to policy planning and implementation that allows for a holistic treatment of an ample and complex problem such as the one depicted here (Christensen & Lægreid 2007; Kavanagh & Richards 2001).

This Handbook provides some insights on the governance challenges of journey-planning platforms that can be helpful to planners in tackling the wicked problem of developing such a tool. Nonetheless, due to the very nature of wicked problems, no definitive response or lesson will be found here or elsewhere. The journey to develop and regulate a journey planning platform is uncertain and tortuous – a wicked one.